Love never quits

The life and ministry of Clarence Jordan

It was 1942, and on the outskirts of the rural South Georgia town of Americus, a radical experiment began. The farm was called Koinonia, and it was to be a first-century version of Christian living in a 20th-century context. It would be a place where everyone — no matter race, gender or wealth — would be welcomed. The guiding principle would be the New Testament concept of koinonia: fellowship, sharing communion.

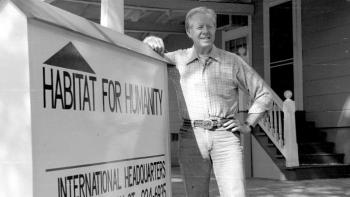

Koinonia Farm was the culmination of the lifelong passions of farmer and biblical scholar Clarence Jordan. On that farm, among rows of pecan trees, after years of struggles caused by boycotts and persecution, the seeds for Habitat for Humanity were sown.

With Koinonia’s roots of racial and economic equality informing the foundation of Habitat’s mission, Jordan’s vision of equality continues to inspire and compel Habitat’s work. “Even though people about us choose the path of hate and violence and warfare and greed and prejudice, we who are Christ’s body must throw off these poisons and let love permeate and cleanse every tissue and cell. Nor are we to allow ourselves to become easily discouraged when love is not always obviously successful or pleasant,” preached Jordan during a sermon titled “The Substance of Faith.”

“Love never quits, even when an enemy has hit you on the right cheek and you have turned the other, and he’s also hit that.”

A path defined

Born in 1912 in Talbotton, Georgia, into a relatively privileged and prominent family, Jordan became aware of economic and racial inequality at an early age. His boyhood home was next to a local jail, and he saw firsthand the inhumane treatment disproportionately endured by Black men there. He observed the unjust sharecropping practices that kept his poorest neighbors, both Black and white, poor, tethered to their stubborn parcel of land and trapped in an endless cycle of debt and poverty.

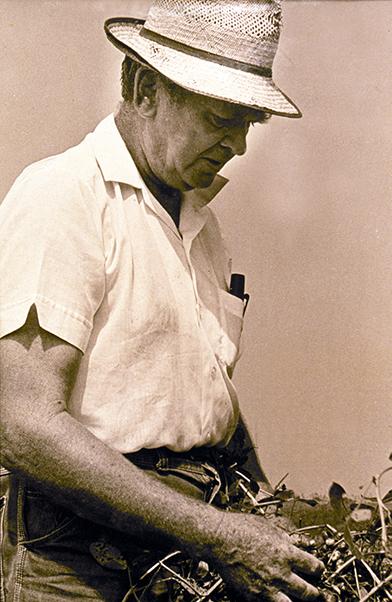

Jordan dreamed of helping families break that cycle. He planned to become a farmer himself. He would teach others techniques and technologies to help increase their harvests and, in turn, their quality of life.

So, in 1929, he enrolled in the University of Georgia’s College of Agriculture. But during his senior year, immersed in his studies and his faith, Jordan’s views shifted. He came to believe that the roots of poverty were not just economic, but spiritual, too — inspiring him to shift from a solely agrarian-focused path to a mission-driven one.

In 1933, after college and during the height of the Great Depression, Jordan began seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. Low on funds but not passion, he worked several jobs while obtaining his divinity degree and, later, his doctorate in New Testament Greek from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Jordan assisted at several Black churches in the city’s West End. He taught and led prayer meetings at Simmons University (now Simmons College of Kentucky), a historically Black college in the city. He served as the director of the Baptist Fellowship Center, working closely with low-income residents.

According to Dallas Lee, a student and friend of Jordan, some of these were Black farmers who had abandoned their faltering livelihoods and migrated to the city in hopes of better economic success. It was these relationships, Lee says, that rekindled Jordan’s dream of helping farmers succeed. “The cumulation of all of this mission work and religious work, particularly his belief that anti-racism had a Biblical foundation, influenced Jordan greatly,” explains Tracy K’Meyer, professor of history at University of Louisville. “After seminary, he felt compelled to put those findings and his beliefs into something tangible.”

After graduation, Jordan and his wife, Florence, a library assistant whom he met and married while in Louisville, returned to southern Georgia. There, in 1942, alongside Baptist minister Martin England, they planted that dream in rural, predominantly Black Sumter County, helping it grow into Koinonia Farm.

Faith in action

In the first several years, the Jordans, England and residing families — about a quarter of whom were Black — worked to establish the 400-acre farm. They were guided by three principles: All possessions were to be held in common. All were to practice nonviolence. All were to be recognized as equal under God.

“The families who came to Koinonia to live in community were searching for a way of life that mirrored their idea of the early church — of sharing things in common, of being there for one another,” says Jordan’s son, Lenny. “It was a bold undertaking, and it wasn’t easy.”

The group experimented with different modern farming techniques and equipment to reduce issues and increase yields. They sold produce in farm stands to establish a base of support locally and started a newsletter to recruit supporters and residents nationally. Side by side, Black and white residents farmed, worshipped and ate together.

By the mid-1950s, as their efforts gained traction, so too did the backlash. With the farm’s ideals and Jordan’s attempt to help two local Black residents enroll in a previously segregated Atlanta business college, they faced intense hostility. Farm equipment was destroyed, hundreds of fruit trees cut down, bullets fired at the communal dwellings, and explosives tossed into one of the farm’s roadside stands. The hate streamed at them from both hooded Klansmen and plain-clothes citizens alike.

Businesses in and around Sumter County enacted a nearly complete boycott against Koinonia. They refused to buy their products or sell them supplies. Local businesses removed all signs advertising the farm, and their insurance company canceled their policy without warning. Customers dropped from the egg route — the farm’s principal source of income at the time — leaving them with several thousand hens and exponentially more eggs.

Speaking years later of the dangers he faced at this time, Jordan acknowledged the risks he, his friends and his family faced. “It scared us, but the alternative was not to do it, and that scared us more.”

The community remained committed to the work, borrowing money to invest in machinery to begin a larger scale pecan processing and packaging operation. They relied on out-of-state orders placed through their national newsletter to bypass the local boycott, advertising under the slogan, “Help us get the nuts out of Georgia.”

By the late 1950s, Jordan wrote in the monthly newsletter that Koinonia now had thousands of pecan customers across the world and not one within Sumter County. The dream survived, if only just barely.

Throughout the 1960s, the farm’s population dwindled as agriculture grew less promising as a livelihood. The few remaining members and residents of Koinonia Farm were active in the civil rights movement, working with like-minded allies in Albany and Sumter counties and providing housing for civil rights workers visiting the area.

While pleased with the advancement of civil rights during this time, the group recognized the systemically racist economic barriers that kept many Black families from fully reaching equality. In one Koinonia newsletter, Jordan wrote that while having the door opened to Black Americans was one thing, having money to spend once inside was also important. The struggle for economic emancipation remained, he said.

A new chapter

Coming from humble beginnings in Alabama, Millard Fuller became a self-made millionaire at age 29. Looking for something more and inspired by a visit to Koinonia, he and his wife, Linda, sold their possessions and began searching for a new focus for their lives. This search led them and their children to move to the farm.

There, Jordan and Fuller pushed each other to think more deeply and more creatively about the injustices of the world and how they could help tear down those barriers that they agreed were keeping Black families from achieving economic equity.

Together, they developed the concept of “partnership housing” — whereby those in need of adequate shelter would work alongside volunteers to build affordable houses. The houses would be built at no profit. Homeowners would pay no-interest loans over a 20-year period. Those payments, along with money earned by fundraising, would create “The Fund for Humanity,” a revolving fund which would enable the continual construction of homes for more families.

The purpose of the fund, Jordan wrote, was “to provide a means through which the possessed may share with and invest in the dispossessed.” The response from their community of supporters was overwhelming and enthusiastic. Land holdings and farm business increased, investments in the housing program grew, and construction crews broke ground.

“There was a stark divide between the quality of Black housing and white housing at the time, even if they earned the same. And housing affects everything you do in life, even your view in life,” Lenny Jordan says of the decision to focus on homes. “All of Koinonia put a ton of energy behind it because it was a way to improve lives, improve equality — both right away and over the long run.”

In the spring of 1969, the Jordans traveled to Ghana. While there, they provided $500 in seed money for a Ghanaian Fund for Humanity, a similar revolving fund to the one at Koinonia whereby families could access funding for home improvements and business projects. Even before the first home in Sumter County had been completed, the impact had spread halfway around the world.

An enduring legacy

That fall, back on the farm, Jordan was working on a sermon in his writing shack, nestled among the pecan trees when he suffered a heart attack and died suddenly. He was 57. Less than two weeks later, the first home built by The Fund for Humanity was completed — a seed of change that Jordan had so staunchly believed in.

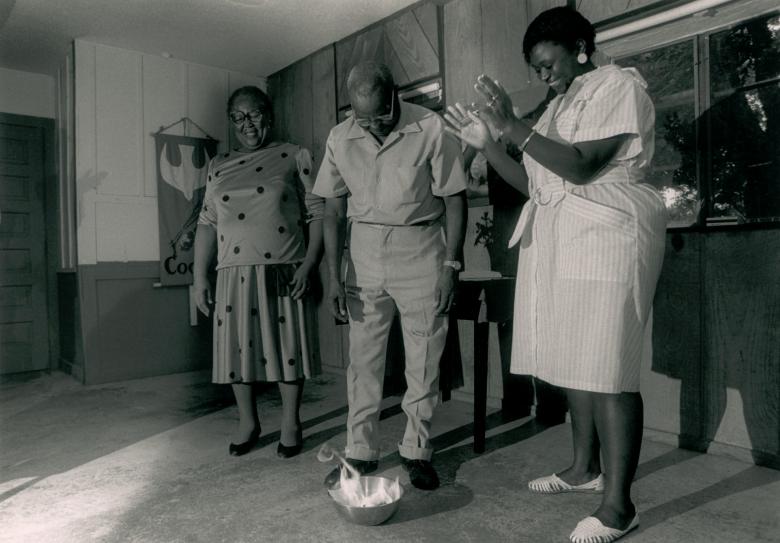

Joseph “Bo” Johnson, one of the first members of the Koinonia community, moved into the home with his family. He and his wife, Emma, faithfully repaid their home loan each month — $25 at a time —for the next 20 years. In 1973, the Fullers took the Fund for Humanity concept to Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo. And in 1976, Habitat for Humanity was founded. In 1989, the Johnsons celebrated the final payment with a mortgage burning ceremony at Koinonia.

Today, with Habitat’s help, families of all races, creeds and backgrounds build and improve places to call home in all 50 U.S. states and 70 countries worldwide. We engage millions of volunteers, advocates and supporters like you, who help families tap into economic equity and prosperity. Who help realize Jordan’s dream by embodying the love that never quits.

Nearly 80 years after its founding, Koinonia Farm is still active and carrying out Jordan’s vision.

Much of this information on Clarence Jordan’s life and legacy came from friends and family of Jordan and Koinonia, as well as the following sources:

- Interracialism and Christian Community in the Postwar South: The Story of Koinonia Farm by Tracy K’Meyer

- The Cotton Patch Evidence: The Story of Clarence Jordan and the Koinonia Farm Experiment (1942-1970) by Dallas Lee

- Restructuring Southern Society: The Radical Vision of Koinonia Farm by Andrew S. Chancey