Africa's future is in its secondary cities

Europe, Middle East and Africa

by Greg Foster, Area Vice President, Habitat for Humanity EMEA | This article appeared on Devex

When most people think about Africa’s cities they name capitals — Nairobi, Addis Ababa, Lilongwe, Kigali and Abuja. There’s good reason. Projections show Africa will have the world’s fastest growing cities over the next 30 years. Today, most have huge informal settlements and slums that some estimates say will triple in population by 2050. If this projection comes even close to that number, Africa’s major cities pose potentially very expensive, long-term problems that instead of boosting economic development could act as a “drag,” limiting growth and exacerbating existing social problems.

For example, recent studies show that some of Africa’s largest cities are actually regressing. While they point to the increasing numbers of people having access to clean water or toilets, they highlight both the higher number and higher percentage of residents who can’t access basic services such as transportation and sewage. In other cities, the massive increase in population has overwhelmed infrastructures causing them to break down.

It would be nice if these were exceptions. Because most sub-Saharan urban dwellers do not have access to at least one of the following amenities — durable housing, sufficient living area, access to improved water, improved sanitation, and secure tenure — it means they live in poverty, according to a United Nations report.

Moving away from ad hoc solutions

The standard urban development process of “plan-service-build-occupy” recognized by the World Bank does not apply to Africa and has led to the degradation of living standards. Where in other parts of the world, creating an urban plan comes well before building and occupying, across Africa the rise of informal settlements and slums stands as testimony to what happens when there is no plan. Considered infrastructure investment directly affects how a city develops, where people live, and where businesses and societal amenities are located.

Urban dwellers need affordable energy, sanitation, solid waste, transport and health care services. Some countries have decided there is little they can do. They have opted to upgrade their cities over a longer period of time, relying on donors to step in and help out.

While this may work, taking a Band-Aid approach delays urban redevelopment, puts a heavy drag on economic growth, and has little or no impact on the people living in informal settlements or slums. And evidence from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development suggests that retrofitting infrastructure can be more costly than starting out with an agreed urban plan.

Two important perspectives need to change. First, governments and donors need to take a long-term approach to developing Africa’s cities. If not, the money that is being spent on informal settlements and slums will have little or no impact.

Second, an inclusive approach where residents’ needs are taken into consideration is required. If not, as cities develop their infrastructure, industrial base and other services, they will (and already are) pushing residents off of what is quickly becoming very valuable property.

Smaller cities have advantages

The future of real economic power and societal development could come from Africa’s secondary cities. That’s not to say the region’s “megacities” will disappear. But, secondary cities may deliver a better future because they don’t have the “baggage.”

That’s why secondary cities are so important. They have more land, are less developed and are usually supported by one large business or a number of smaller ones. This means they can support their population and, with a little investment, could offer the best hope for reducing migration to the megacities, providing well-planned and sustainable communities, while boosting economic development. Secondary cities offer a real opportunity to develop communities that can meet and exceed the New Urban Agenda to be adopted at Habitat III.

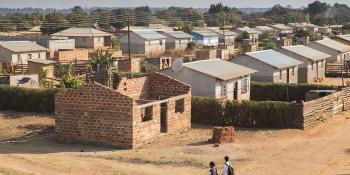

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak with a leader of one of Africa’s secondary cities. He said that when the country gained independence in the early 1960s, his city had 30,000 residents and 85 kilometers of paved roads. In 2000, there were about 70,000 residents and 95 km of paved roads. Today, it has more than 490,000 residents, of which, if the national average of 60 percent holds true, 290,000 live in informal settlements or slums. And, out of 95 km of paved roads, 65 km need major repair or replacement.

Nevertheless, he’s optimistic. He and his fellow city leaders are developing a realistic and workable urban plan that includes roads, energy, water and sanitation. Because authority is being devolved to municipalities, city leaders are eager to find ways to get the area’s residents into homes and planned neighborhoods and out of informal settlements. There are three reasons. The first is taxes. Planned neighborhoods bring in tax dollars from homeowners and businesses. Second, planned neighborhoods are easier to supply with utilities, schools, hospitals and parks. And, third, planned neighborhoods turn into communities that offer residents the ability to find employment, raise a family, and build the city’s future.

The key, he said, is getting the right actors involved. In his case, town leaders have asked the international community to help document property ownership, land rights and tenure. They have reached out to leading private sector leaders, making it clear the city will upgrade water, power and sanitation infrastructure to ensure the success of their investments. And, they are looking for new types of housing, seeking new, better and less expensive solutions to get the residents on the property ladder. They are firm believers in the “for every house built, five jobs are created” view held by many in both the private and public sectors.

Empowered cities make their own futures

At a recent Sustainable Development Goals meeting in Rome, cities of all sizes presented their challenges and solutions. A key turning point for each was when planning and taxation powers were devolved from the central government. This enabled them to plan their community’s futures and pay for them out of tax receipts. Taking this a step further, many secondary cities are looking into funding their major projects such as electricity generation, water and sanitation, and roads through municipal bonds.

Secondary cities usually have a number of economic advantages over megacities. They can usually rely on a fairly resilient set of large industrial or agricultural companies. Some are conglomerates, while others seek to build in value-added to increase the level of profit that will remain inside the country. Others are market cities that are key hubs playing a substantial role in trade, culture and education on a subregional level.

What is clear is that the time is right for re-evaluating where investments and funding is being made. Africa’s megacities will continue to draw people. But the region’s secondary cities may become the economic powerhouses and social centers of the future. They have all of the right ingredients for success and could become places where people have the opportunity to avoid the problems associated with megacities, build a strong, stable communities, and have decent places to live.