The difference a home can make

Addressing stigma and the needs of the most vulnerable

At 12 he was told he had leprosy. He couldn’t afford or get regular treatment. And, it was only in his mid-twenties that Tegegn Bogale Selegn was cured. It left both physical and social scars.

Outwardly, his hands suffered the most. He has no fingers which made it difficult for him to provide an income for his family. “All I could do was beg in the street. Sometimes, the church would help us.” But it was the stigma and discrimination that was the hardest to take. “Being healed didn’t mean life was much better,” says Tegegn. “People would still avoid me and that was terrible. At one point I was even thinking about suicide.”

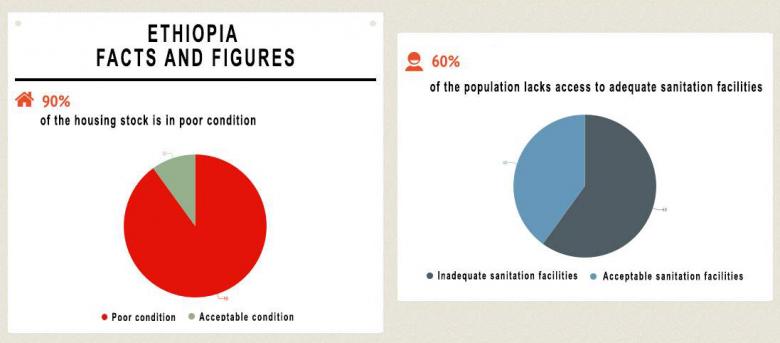

Tegegn lives in Kombolcha, a city of about 100,000 people in Ethiopia’s Amhara region. The area grabbed media headlines around the world during the famine in the ‘80s. Today, while many of Kombolcha’s inhabitants are small-scale traders, the majority are considered low-income earning less than $45 a month and live in substandard housing.

About eight years ago, Tegegn watched as Habitat for Humanity Ethiopia started building a home in Kombolcha. He had heard that leprosy survivors were eligible for housing and wanted to know more.

“After speaking to the Kombolcha Community Committee and registering, I still didn’t think I would actually ever get a house”, he said. “I waited six months before I heard that construction would begin.”

Ali Mohammed Ali, the chairman and founder of the Community Committee who works with Habitat for Humanity, used to live in a shack above a sewer. “My family was always sick,” he said. “The smell came through the cracks in the floor and the unhealthy conditions made things worse.” Now that Ali and his family have moved into a new house that has changed. “We are rarely sick.”

Others, like Tegegn, have many more challenges.

“People like Tegegn have a family, no income and no proper housing. We held a series of meetings and information sessions in the community,” Ali commented. “This created awareness about people with disabilities, such as Tegegn, before they became neighbors.” The sessions provided critical information on the transmission of leprosy, a bacterial disease that slowly eats away the skin and nerves, causing deformities and disfigurement.

“It was widely believed that leprosy was easily transmittable or that it was a curse,” commented Ali, “when in fact it comes from overexposure to another person who is suffering from it.” The sessions had a noticeable impact on other families considered to be vulnerable— the disabled, orphans and those affected by HIV/AIDS.

Today, Tegegn and his family live in a home with a 4 by 4 meter living room, and a 2.5 by 4-meter bedroom. “It’s like living in a palace,” said Tegegn. “We now have a much more normal life.” His wife Taitu, who never had leprosy herself, was also discriminated against because she was married to Tegegn.

Receiving the house created the space and time for Tegegn to think about himself and his life. “I started to think about supporting my family after getting the house,” he says. “I learned I could make ropes.” The strong rope Tegegn weaves is sold for $1 dollar and takes two days to make. He and his family also grow papaya and coffee in their compound.

Although the Habitat houses come with their own toilets, which have significantly improved health conditions, there is still the need to bring water to all the houses.

“I realized that even though my hands are disfigured, I can still do something. I can tie ropes so I started a new business.”— Tegegn

So far, more than 200 homes have been built, but there is a long waiting list and the project needs to be scaled up. The Habitat Ethiopia and the Community Committee partnership works well and is supported by the local government, but scaling up is hard. “We try our very best to secure land,” said Ali, “but if there is no construction going on, the local government is allowed to take it back and use it for other projects. We just need the resources.”

Learn more about Habitat for Humanity’s work in Ethiopia.