Why they matter: Local and state zoning reforms

Localities can update their zoning codes in various ways to reduce development costs and encourage home affordability across a wider landscape.

Localities can update their zoning codes in various ways to reduce development costs and encourage home affordability across a wider landscape.

Housing trust funds offer the advantage of having a stable, flexible source of funding which can be a critical advantage for communities looking to address the home affordability needs across the housing continuum.

General obligation bonds offer a flexible way to finance a wide range of affordable housing activities, such as home construction, repair programs and down payment assistance.

Whether you’re a do-it-yourself hobbyist or a construction professional, the ReStore is a unique place to find the tools, appliances and materials you need to help complete or inspire your next building or decorating project. And those finds, in turn, help build so much more.

Whether you’re a do-it-yourself hobbyist or a construction professional, the ReStore is a unique place to find the tools, appliances and materials you need to help complete or inspire your next building or decorating project. And those finds, in turn, help build so much more.

That’s because, once an item sells, the proceeds help fund Habitat’s local work, so more families can build or repair a place to call home. From 2011 to 2021 alone, Habitat ReStores in the U.S. have generated more than $1 billion to further Habitat’s work both locally and internationally, through Habitat’s tithing program.

Here’s a look at just some of the fantastic finds that, while passing through Habitat ReStores, have helped families build or improve the places they call home over the past three decades.

When Alice Linton went to Habitat Greater Toronto Area’s Scarborough ReStore many years ago while she was restoring a historic home nearby, she wasn’t sure what she would walk out with. “I certainly didn’t think it would be a fireplace,” she says. But that’s part of the wonder of the ReStore, she adds. “Sometimes things just find you.”

The fireplace had been painted white, but otherwise seemed to be in perfect shape. At home, she meticulously stripped away the layers of paint to reveal the beautiful golden oak underneath. She also discovered a handwritten inscription on the back that said the piece had been made in Ohio in 1862.

A close friend and local carpenter completed the restoration process for Alice and treated the fireplace with beeswax to protect it. Alice refinished the metal parts of the insert, taking care to preserve the unique, hand-painted tiles. “It turned out stunning,” she says of the effort. “The golden oak just shines.”

Years ago, the fireplace accompanied Alice on her move to California, joining her first in her home and then in her office, where more people could enjoy it. Alice is planning another move soon, this time to Europe, but the fireplace won’t be making the trip. “My daughter already called dibs on it,” she says with a smile.

A chance discovery at the Habitat Peterborough & Kawartha Region ReStore in Ontario, Canada, resulted in the return of an important piece of family history.

Ninety-two-year-old Catherine Allen was “astonished” to be reunited with the First World War medals honoring her late father and grandfather. Believing them to be in the possession of another relative, she didn’t even realize they were missing before she was contacted by Habitat Peterborough board member Jill Bennett who had spent weeks investigating their origins.

The medals belonged to Allen’s father, George Raymore Scott, a physician and medical officer, and her maternal grandfather, the Rev. A.J. Vining, a war chaplain. They were found in an old plastic food container that was destined for the trash, but when a ReStore employee opened it to ensure it was empty, they discovered a pouch containing the medals.

This Swiss-made wooden bathtub and a matching set of wooden sinks were donated to the Habitat Vail Valley ReStore in Colorado. They are made from wood veneers that are compressed under pressure and saturated with a special resin. The tub alone retails for $24,000. The set of three was put on the ReStore sales floor for $12,000 and sold in less than a month.

A long-time donor picked up this ornate prayer kneeler at a local estate sale and donated it to the Lakeland Habitat ReStore in Florida.

“We see some pretty unique things come through the ReStore, and this is definitely one of them,” says Claire Twomey, CEO of Lakeland Habitat.

Dozens of windows from the Habitat ReStore Southeast in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, were collected by a customer who used them to create this impressive greenhouse in his backyard. The DIY project will help his garden flourish by protecting it from extreme temperatures and unwanted pests, all while diverting items that otherwise might have been sent to the landfill.

“My wife saw a multi-color floor on a stage and thought it was beautiful,” Tom Amadio says, explaining the inspiration for their home’s new flooring design. At least half of the hardwood for the project — a mix of cherry, maple, poplar, red oak and white oak — came from different trips to the Habitat Sault Ste. Marie ReStore in Ontario, Canada. “It ended up saving us roughly $4,000,” he says of the effort. And the bespoke conversation-starting floor that now spans their living room, dining room and kitchen? Priceless.

When Howard Kirby purchased a matching couch and ottoman from Saginaw-Shiawassee Habitat’s ReStore in Owasso, Michigan, he was just looking to spruce up his man cave. But finding the ottoman a bit lumpy and uncomfortable, his daughter-in-law unzipped the cover to discover the culprit: $43,170 in cash stuffed into the cushion.

Although an attorney advised Howard that he had no legal obligation to return the money, he instead called the Owasso ReStore to track down the original owner.

Rick Merling, manager of the Owasso ReStore, found Kirby’s decision inspirational. “To me, this is someone who, in spite of what they’re going through, in spite of their own needs, has said, ‘I’m just going to do the right thing,’” he told local news station WNEM.

It turns out that the furniture had come from a woman who had donated her grandfather’s couch after he had passed. She was shocked to learn of the stowed away cash, recalls Merling. Howard met her at the ReStore and returned her late grandfather’s savings. Now no longer lumpy, the ottoman and couch stayed with him.

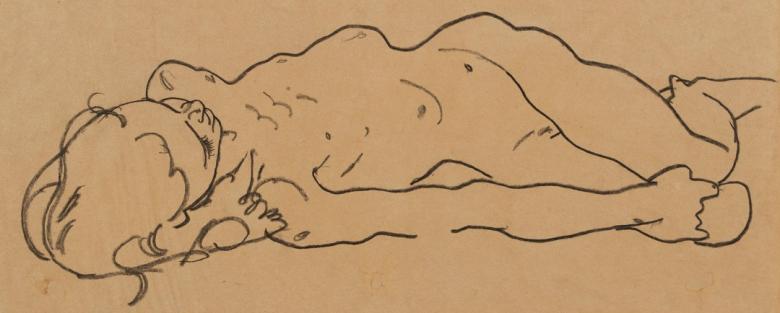

A line drawing purchased at the Habitat New York City ReStore for $80 turned out to be a previously unknown artwork by major 20th-century painter Egon Schiele worth between $100,000 and $200,000.

After discovering its historic value, the buyer, a ReStore regular who wishes to remain anonymous, sold the pencil drawing and donated a portion of the proceeds back to Habitat New York City.

“I can’t help but think that were it not for the Habitat NYC ReStore, this piece of art history might have ended up in a landfill, lost forever,” Karen Haycox, CEO of Habitat New York City, told The Art Newspaper. “It has been given new life.”

Habitat Anderson ReStore staff in South Carolina were surprised to find an unmarked box dropped off by an unknown donor that contained roughly 100 unique canes featuring a variety of wood and carvings, including this one of a wine barrel concealing intricate miniature wine bottles and glasses.

Jim Ward, a volunteer at Habitat South Georgian Bay’s Collingwood ReStore in Ontario, Canada, is the creative mastermind behind this series of ReStore finds that have been upcycled into lamps, sculptures and more. Jim often donates his pieces to the ReStore’s annual silent auction to help raise even more money for affordable housing.

This rainbow of porcelain sinks represents just a few of the 5,699 items donated to the Habitat Springfield, Missouri ReStore from 2019 to 2020.

“I shop at the Sangamon County Habitat ReStore often. What I enjoy most is the thrill of never knowing what treasure I might find. Once, I found three pieces there — a glass cabinet and a hutch and sideboard. I put the glass cabinet together with the sideboard, painted it all black, sanded it and distressed it, but left the shelves natural. It’s currently in my dining room, and most of the things it holds — a brass reindeer, brass candlesticks, copper tea kettle, gold-rimmed glasses, marble cheese board and glass punch bowl — are ones I’ve found at the ReStore.”

— Elizabeth Kallembac, Springfield, Illinois

“I love reusing things and have been shopping at the ReStore since they opened here in Topeka. Heck, I drove to Lawrence, Kansas, before we had one in Topeka. I picked up the sink and countertop, the tile for the backsplash and light, and the shades in one trip and completely redid my bathroom with them. I love that I can find pieces that fit the time period of the old house I live in.”

— Ron Lopez-Reese, Topeka, Kansas

“I love thrifting in general, but I especially love how affordable the prices are at ReStore and the variety of items they offer. I would go to the Habitat Charlotte Region ReStore frequently just to browse and try to find something unique. When I saw these chairs, I had to have them! We eat every meal together as a family, so we sit on them for breakfast, lunch and dinner. We use them when we sit at the table and do puzzles together or art projects for school. We sit there when our family comes over to have a cup of tea and chat about life. They’re at the center of our home.”

— Sam Schuerman, Mooresville, North Carolina

From a vintage sideboard to a collection of hand-carved canes, you never know what fantastic find awaits you at the ReStore. With an ever-changing inventory based on local donations, it can be a surprise with every visit. But with every purchase supporting Habitat, no matter what you treasure you discover, you can be sure that you’re making difference in your local community every time you donate and shop.

With a shortage of affordable housing in communities across the U.S., it is more important than ever that we help low-income homebuyers learn about and take advantage of down payment assistance programs and the support they provide.

Code enforcement is a key way we can work together to provide safe homes and neighborhoods that create opportunities for everyone to succeed.

The need for global housing is so vast and the issues that surround it are so complex that Habitat works in many ways to partner with families and communities to create sustainable and sweeping change. That’s how we will realize our vision of a world where everyone has a decent place to live.

Most people know Habitat for Humanity as a global nonprofit that partners with families to build or improve decent, affordable places to call home. That’s at the very heart of what we do.

The need for global housing is so vast and the issues that surround it are so complex that we also work in many additional ways to partner with families and communities to create sustainable and sweeping change. That’s how we will realize our vision of a world where everyone has a decent place to live.

Learn more about just a few of these efforts:

Habitat’s Terwilliger Center for Innovation in Shelter works to catalyze the private sector’s responses to the global need for affordable housing. Most of the world’s people build homes bit by bit as their families grow, as their limited finances allow and without access to the formal housing market. In response, Habitat works to expand innovative solutions, services and financing so low-income families can improve their shelter more effectively and efficiently.

Through ShelterTech, for example, the Terwilliger Center identifies and supports fresh ideas and start-ups working in the housing space. Participants receive access to expertise and catalytic funding to grow their businesses, plus the opportunity to grow their professional networks. Since the first accelerator, held in Mexico in 2017, ShelterTech has expanded to Kenya, India, Southeast Asia and the Andean region of South America.

Solutions have emerged from the program including sustainable waste processing for areas without sanitation services, 3D printing technology for home construction, a peer-to-peer lending platform for first-time homebuyers, and using augmented reality to connect families to designers and builders for remodeling and construction projects.

Through Habitat’s MicroBuild Fund, the Terwilliger Center also increases the availability and accessibility of housing microloans in 32 countries where financial institutions and services are limited. Microloans are different from traditional loans in that they have relatively short repayment periods, are for smaller amounts and require little or no collateral. In collaboration with financial partners, Habitat’s Terwilliger Center makes microloans available for families looking to expand or improve the quality of their homes, purchase land, or meet other housing-related needs.

In addition to raising our hammers, Habitat also raises our voices through extensive advocacy efforts in the U.S. and around the world. These efforts seek to improve what might be less visible aspects of housing like laws, regulations, systems and policies that affect adequate and affordable housing.

Within the U.S., nearly 400 Habitat affiliates are leading the effort to eliminate barriers to decent housing as part of our national Cost of Home campaign. Working together over the five-year advocacy campaign, we aim to influence policies that will help 10 million individuals access an affordable place to call home. Now two years in, despite the ongoing housing challenges, significant progress has been made. From calling for increased investment in housing trust funds to championing mortgage relief for homeowners impacted by COVID-19 across all 50 states, advocates have used their voices to fight for solutions to address the housing needs in their communities.

Globally, we use our voices to engage at all levels of government, and, in partnership, we work in five key areas: ensuring access to adequate housing, improving housing finance options, strengthening land rights, enabling stakeholder engagement and creating resilient housing.

From strengthening women’s land rights in Zambia to encouraging the European Union to prioritize housing in its global development policies to calling on governments around the world to protect housing as a first line of defense during COVID-19, Habitat is committed to creating more equitable housing policies and systems to increase the scale at which we work.

Habitat helps families across the world improve their water, sanitation and hygiene systems, including during emergencies like disasters and COVID-19. We help residents install water kiosks in the heart of communities, creating access to clean water for washing, cooking and bathing. In addition to reducing health concerns posed by unsafe water, the kiosks also reduce the timely burden of fetching it, freeing residents from hours walking miles while carrying heavy loads of water, often from compromised open sources.

Every WASH initiative is developed to meet the needs of a given community. In Guatemala, where an estimated 85% of wastewater is left untreated and is often discarded into local water sources, Habitat Guatemala adds sanitary latrines to existing homes to reduce pollution and improve the health of families, farmlands and communities.

Habitat Cambodia staff and volunteers lead children through hygiene demonstrations to encourage improved practices. Habitat Macedonia has extended microloans to help hundreds of rural villagers eliminate their dependence on hazardously placed open wells and instead connect to their region’s safer central water system.

Habitat’s decades of work have shown us people thrive when they have a safe and stable home in a safe and stable community. For this reason, it is important to think about the whole neighborhood — not only the house — that Habitat homeowners and other residents will call home.

Through our neighborhood revitalization work, Habitat helps engage partner organizations and empower community leaders to respond to the needs and aspirations of their neighborhoods. By ceding the leadership role to residents, we can help ensure that this transformational effort will continue long after Habitat. To guide their efforts, residents use Habitat’s Quality of Life Framework, a data-driven and customizable approach to improving neighborhoods. This framework provides a road map for holistic change based on the unique gifts, dreams and concerns of each individual neighborhood.

For communities where safety is a priority, the framework helps residents set out steps to reduce the opportunity for crime — such as establishing after-school programs, improving lighting in public spaces or setting up a neighborhood watch. For a community in a food desert, the framework might lead them to set up a community garden or start a local farmer’s market to help them increase access to healthy food.

Whatever path they decide on together, through the bond of their shared neighborhood and the camaraderie and trainings offered by Habitat’s neighborhood revitalization work, community members have an increased capacity and motivation to overcome barriers to sustainable change.

Rather than always starting new, Habitat has found that big changes in accessibility, affordability and safety can be accomplished through smaller cost-effective repairs and renovations that allow vulnerable homeowners to remain securely in their homes.

In the U.S., many older adults find their homes unsuitable for their needs or lack access to resources to make their homes livable and safe as they grow older. That’s why Habitat developed Housing Plus, a comprehensive aging in place strategy that uses a person-centered approach considering everything from lifestyle to type of home and allowing Habitat to address needs holistically.

In many parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, energy poverty — where residents either pay an exorbitant amount of their income to access utilities or are forced to go without — is a widespread issue that leaves those with the lowest incomes trapped in a perpetual cycle of poverty. But through the Residential Energy Efficiency in Low-Income Households project with USAID, Habitat is able to help families in Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia make energy-efficient improvements that reduce their energy costs and improve their comfort and health.

In Guatemala, many families who have been excluded from basic services like electricity rely on indoor wood-fueled fires to prepare meals. The smoke from these fires lead to high rates of respiratory illness, especially among infants — which can prove fatal. Habitat Guatemala works with these families to install smokeless stoves, which eliminate indoor smoke and lower the risk of burns from cooking over an open flame.

They also cut the amount of wood needed to cook almost in half, saving families money and time. The stoves are often combined with a water filter and sanitary latrine to elevate the overall health of the home and the family inside. Families are involved in the entire process and learn how to assemble, use and maintain each product.

From investing in start-ups that disrupt the status quo to enacting policies that provide clear pathways to homeownership to partnering with families in new and exciting ways, Habitat can extend our reach and increase our capacity to help make sure that everyone has a safe, decent and affordable place to call home.

As part of Habitat for Humanity’s ongoing hurricane recovery efforts, generously supported by AbbVie, Habitat works with local businesses to help families in Puerto Rico repair homes affected by hurricanes Irma and Maria.

In the coastal town of Salinas, Puerto Rico, Javier Cosme, a carpenter for PEC Contractors, worked to patch holes in a roof that had been damaged by Hurricane Maria. Whenever it rained, water leaked into the rooms below, affecting the day-to-day lives of a family of three. Javier was making the repairs as part of Habitat for Humanity’s ongoing hurricane recovery efforts, generously supported by AbbVie, a research-based global biopharmaceutical company and one of the largest employers on the island.

The family was so grateful for Javier’s work to repair their roof, they offered him and his crew lunch every day. “They want to give what they didn’t have, you know, to make us feel well, when on the contrary, we’re trying to help them,” says Javier, in his native Spanish.

Since 2019, Javier has worked with PEC Contractors, a local small business, to help families in Puerto Rico repair homes affected by hurricanes Irma and Maria. “I solve all the situations that come up along the way in the project,” says the 43-year-old father of two, who does a “bit of everything” in his role as a carpenter, including brickwork, painting and electrical work.

Like the families he helps, Javier understands the importance of having a safe place to call home. After Hurricane Maria, he and his family were forced out of their own house, which was severely damaged by the storm. “I’ve struggled to lift my home back up because of the same thing, but I have the knowledge and ability to fix it,” says Javier, who has been working with his family to rebuild. Javier taught his wife, Karla, his 19-year-old daughter, Lyneshka, and his 18-year-old son, Javier, construction skills to help bring their home back to life. “They learned everything,” Javier says proudly. “From taking down what was left, which was wood, to binding cement to laying blocks to everything.”

After the unprecedented 2017 storms, AbbVie donated $50 million to Habitat to help families and communities recover through a holistic program that focuses on home repairs, helping homeowners secure land tenure, advocacy work — and workforce development.

“We are committed to helping families affected by the devastation of Irma and Maria by building and repairing homes in Puerto Rico, and ensuring safe, and resilient shelter,” says Claudia Carravetta, vice president, corporate responsibility and global philanthropy at AbbVie. “This commitment includes creating opportunities for training and employment, which is necessary to help the Puerto Rican economy and families fully rebuild after these disasters.”

“Our work in Puerto Rico targets home repairs, and it also helps build small businesses,” says Kevin Campbell, managing director of Habitat’s Puerto Rico recovery program. “It’s all part of a purposeful strategy to increase the capacity of the construction labor force by training new workers and contribute to the economy by hiring local contractors.”

Ultimately, 650 homes will be repaired through the hurricane recovery program.

“Our work in Puerto Rico targets home repairs, and it also helps build small businesses. It’s all part of a purposeful strategy to increase the capacity of the construction labor force by training new workers and contribute to the economy by hiring local contractors.”— Kevin Campbell, managing director of Habitat’s Puerto Rico recovery program

Businesspeople like Elizabeth Sánchez, owner of PEC Contractors, have benefitted from the steady work the Habitat program brings to them. Javier, who she describes as having a “gift with people,” was one of 10 new team members she was able to employ as a result of working with Habitat. So far, her company has repaired 38 hurricane-damaged homes. “Thanks to Habitat, and to the growth that I’ve had, I’ve been able to buy a lot of equipment, like trucks, that I didn’t have previously,” says Elizabeth.

In addition to working with local small businesses, like PEC Contractors, Habitat recently partnered with a local private university to create Habitat Builds Puerto Rico, a 5-week program that teaches skills like masonry, plumbing and carpentry for those interested in entering the construction field.

Javier credits working to repair homes with Habitat as a key part of helping him to support his family throughout their own rebuilding process, as well as allowing him to do good in the world. “It’s benefitted me,” says Javier. “But also it’s being able to serve and be useful to other people.”

He hopes to put the final touches on his home soon. “I still need to finish the bathroom and put up doors and windows,” Javier says. He and his family can’t wait to celebrate holidays and milestones again under their own roof.

Like so many homeowners affected by the storms in Puerto Rico, Javier is looking forward to a bright future in safe and stable home where his family can thrive. With AbbVie’s support, Habitat continues to pursue multiple avenues to that future by creating economic opportunities for workers like Javier and Elizabeth and making more repairs possible for the families they serve, ensuring that both families and communities are more resilient to future disasters.